To evaluate a body of creative work produced by an artist during a specific period in time, an understanding of concurrent social, cultural, political, and economic conditions is imperative. The nature of the photographic materials produced by American photographer, Walker Evans (1903-1975), during his tenure with the United States Resettlement Administration [RA]/Farm Security Administration’s [FSA]1 Historical Section (1935-1938) provokes the opportunity for consideration of several presumable though dissimilar narratives. At the intersection of the Great Depression and the Roosevelt Administration’s ascent to power (1933), Evans fulfilled a role as a photographer employed under the auspices of a bureaucratic agency. During such devastatingly catastrophic socio-economic times, Evans was wise to secure and accept stable employment with the RA/FSA. All the while Evans, who had already defined his vocation as an artist and achieved recognition for his craft by contemporary arbiters of culture, contended with the challenge of maintaining his own aesthetic within a government engineered apparatus. Given Evans’ lengthy career, the years 1935-1938 may appear to be a transient moment in time. However, they were among his most prolific, and the types of images and narratives he produced for the files that he created for the RA/FSA impart an important window into further understanding his character.

The type of photographic documentation sought by authorities within the RA/FSA was punctuated by a necessity for publicity materials that would serve to confirm the validity of the Roosevelt Administrations’ New Deal programs and cement greater constituents. An aggressive emphasis was placed on the RA/FSA’ Historical Section to produce materials that illuminated the successes of recovery efforts throughout rural America. For Evans and other photographers associated with the RA/FSA, the precise syntax for production of images was filtered through a lens of prescriptive measures and subject to the largesse of the Roosevelt administration’s dissemination strategy. Allan Sekula has made an appeal to socially conscious viewers and practitioners of the arts to critically assess the close historical partnership of documentary artists and social democrats, arguing that there is much to be learned from our “Progressive Era and New Deal predecessors”.2 Between 1935-1938, the files created by Evans for the RA/FSA Historical Section offer much enlightenment on how he exercised his artistic practice in the face of extreme social, political, and historical circumstances, and how he managed to deliver his vision of America within this framework. Although Evans’ license to freedom of creative aesthetic was conditioned by a framework, the images he produced invoke three worthy narratives for discussion: art, social documentary, and propaganda.

Walker Evans the Person

Among the group of photographers employed by the RA/FSA Historical Section, Evans was recognizably the most skilled, and the group was enigmatically shaped by the individual capabilities of the participants. Irrespective of the Roosevelt Administration’s influence on the Historical Section, the individual traits and personal histories attributed to the photographers offer an important context within which to evaluate the successive narratives produced by the photographers. In the case of Evans, who by 1935 had already been accoladed for his achievements in the world of contemporary photography, a level of leniency and independency within the RA/FSA administration was accorded to him. Peter Turner has aptly described the nature and outcome of Evans’ typically artistic character operating within a typically government administration:

“It was a way for the artist to do the work he wanted with a steady pay check, and he supposedly did not have any real regard for the desires of his supervisor. The photographs‘ context was one of factual documentation, but in truth they are examples of Evans doing what he was best at distilling the American experience. The wilful individualism of Evans was contrary to the other FSA workers, as he was an artist/photographer, and as such, he could not fully comply with the directions given by a supervisor.”3

Throughout his tenure with the RA/FSA, Evans was inspired by an intense desire to artistically explore the American vernacular and independent beyond bureaucratic toleration; his images bearing more artistic elements than reforming. Unsurprisingly, he was asked to leave the Historical Section when a reduction in government funding provided the opportunity. Evans’ artistic aesthetic and opposition to conformity evolved as a consequence of his exposure to various social networks. Evans received his first camera, a Kodak Brownie, during his youth – a time that was punctuated by numerous emotional and personal upheavals. His earliest amateur photographs reveal a sense for capturing people unaware, and the posture of a covert photographer would later resonate in his RA/FSA photographic materials. It wasn’t until the late 1920s that Evans began to fully embrace his artistic vocation. Coming of age during a time that was shaped by post-World War I economic prosperity, Evans indulged in a sojourn abroad to Paris, in 1926. Belinda Rathbone writes that Evans went to Europe with the aspirations of becoming a writer, and sought out such American luminaries as: Ernest Hemingway, Dorothy Parker, T.S. Eliot, and Man Ray. Rathbone highlights that Evans was a persona non grata among them.4 During this period, Evans experienced an epiphany and channeled his creative energy into a renewed interest in American culture. Evans felt no disdain for his shortcomings as a writer, and classical literature, particularly the works of Gustav Flaubert, Charles Baudelaire, and James Joyce, would remain a defining influence on his creative aesthetic. Evans stated that he made no distinction between literary and visual artists, and that the individual images and the fusion of the separate images into books resemble the units and flow of a row, especially the work of Flaubert: “I know now that Flaubert’s aesthetic is absolutely mine…his realism and naturalism both, and his objectivity of treatment; the non appearance of author, the non subjectivity.”5 The inspiration behind Evans’ vision of America and aesthetic would eventually be evidenced in the RA/FSA Historical Section’s content.

Upon Evans’ return the United States, Evans married himself to the enrichment his vocation as an artist, and soon acquainted himself with significant literary figures, artists, and socialites. The likes of James Agee, Hart Crane, Paul Strand, Ben Shahn, Lincoln Kirstein, and Charles Flato were among his social circle, and his aesthetic was energized by their influence. Evans’ desire to explore and comprehend colloquial American culture found a medium for expression in photography, where the observer and the observed met at eye-level. At the intersection of Evans’ maturation and recognition of his artistic vocation, the dramatic effects of the Great Depression commanded unforeseen socio-economic conditions upon the American people. Conditions were further exacerbated by dramatic shifts in politics culminating in the establishment of the Roosevelt Administration (1933-1945). Evans would soon embark on a precarious exploration of his aesthetic within a new polity that facilitated unforeseen opportunities for creative expression in the form of New Deal agencies.

Shifts in Political Power: The Roosevelt Administration and the New Deal

Positioning Evans within the socio-political framework in which he functioned between 1935-1938 enhances the capacity to comprehend the narratives he produced. The rise of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his Administration to power in 1933 was laden with controversy. Conservatives and advocates of limited government protested against the institutionalization of federal policies aimed at cementing a social welfare state. Although former president Herbert Hoover’s decline in popularity was largely conditioned by the great economic crash (Black Monday, October 29, 1929), his policies also reveal tendencies towards the centralization of government power and stabilization of social welfare state. America was in a period of transition and Evans was there as both observer and participant.

During the Great Depression, the Roosevelt Administration provided relief to economic crisis pervasive throughout American society in the form of New Deal agencies. Policies and governmental structures postured in socialism and engineered by the Roosevelt Brains Trust also supported the creative arts in unprecedented ways. Between 1933 and 1943, various government programs sponsored and encouraged the proliferation of the creative arts, employing artists, musicians, writers, actors, filmmakers, photographers, and dancers.6

The RA (1935-1937) was among the New Deal agencies established to relieve economic strife, and the Historical Section was created to employ photographers whose task was to function as a documentary network in the service of the Roosevelt Administration. Evans’ employment with the RA’s Historical Section offered him an opportunity to financially survive during the Great Depression, and to participate in one of the most controversial government supported creative programs in American history.The RA was the precursor to the more commonly known FSA (1937-1942). The RA was headed by Rexford Tugwell, an influential economic advisor within the Roosevelt Administration, and was established in response to the ineffectiveness of the New Deal’s main agency, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration [AAA]. The AAA had concentrated on the interests of country’s largest farm producers, all of whom had arresting influence in Congress due to the domineering positions they held within major farm organizations. The aim of the RA was to relocate seemingly hopeless rural Americans who had been subject to the effects of the dust bowl storms to either better lands or planned suburban communities. The RA also offered services to sharecroppers and tenant farmers who otherwise would have had few prospects for relief. By 1937, the RA had proven to be negligent in facilitating the relief effort, and Congress passed the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenancy Act, thus creating the FSA.7 Both the RA and FSA proved to be ineffective and financially disastrous operations. All the while, between 1935-1938, the Historical Section exhibited utmost efficiency in the ability to document and support the successes of the Roosevelt administration’s policies. During this time Evans created a wealth of documents suggestive of the struggles he contended with and the aesthetic he so desired to explore. The principal force behind Evans’ term and the vigour with which the RA/FSA’s Historical Section functioned was Roy Stryker.

The RA/FSA, Roy Stryker and Walker Evans

Tugwell’s impetus to create an Historical Section within the RA was driven by an awareness of the potential agency illustrative materials could have on both Congress and the public at large. Stryker, a colleague of Tugwell versed in economics and the communicative power of photography, was hired to direct the Historical Section. Stryker’s vision of American society had been influenced by the last days of the greater American frontier. He had been raised in the primitive atmosphere of Southwestern cattle country, was fluent in American agricultural history, and taught economics at Columbia. Stryker had also read Frederick Jackson Turner’s seminal essay, On the Significance of the Frontier in American History. The work’s fundamental arguments imbued his vision. In the midst of the Depression, Stryker’s portrait of America was one that included “all aspects of American rural life, with an emphasis on what had gone wrong: deforestation, soil erosion, migrant fruit pickers, and hungry children”.8 Stryker’s vision for the Historical Section went beyond the realm of simply satisfying the demands of public relations. Under Stryker’s aegis, a sensitive and contemporary portrait of rural America was authored by a talented and mindful cohort of individuals that included Evans among them. A discussion on Stryker’s authorship of the RA/FSA file, his relationship to politics, documentary photography, and print media networks exceeds the context of this discussion, though it is pertinent to note that he commissioned and prescribed nearly all the documents created for the RA/FSA in the form of shooting scripts.9

Under the auspices of Stryker, the Historical Section of the RA/FSA produced one of the most important and substantial social history archives in American history.10 Stryker revered Evans’ distinguished artistic capabilities, and hired him almost immediately, noting that Evans was “one of the best photographers in the country for the job of photographically documenting American history”.11 Evans was given the title of senior photographer and the highest salary. Between 1935-1938, Evans and Stryker clashed on numerous fronts; Evans abhorred Stryker’s demands for scripted production and Stryker looked disapprovingly upon Evans’ low level of productivity. Evans adopted a passive aggressive stance towards his director’s incessant formulaic instructions and continued to pursue his assignments with obvious independence. Evans was the first photographer to be dismissed when budgetary difficulties arose, and it is more than likely that Evans’ dismissal came as a relief for both parties. Their lack of camaraderie and disparate interests in the Historical Section’s purpose were markedly clear.12 Alan Trachtenburg has commented on Evans’ term with the RA/FSA and noted that “Evans found a way of returning the image to everyday culture, employing what he called documentary style in the service of a psychology of form”.13 The nuanced narratives enabled by Evans undoubtedly offer a deeper understanding into the world of an artist whose aesthetic was subject to engagement with contemporary societal conditions and government bureaucracy.

Images as Art

During the twentieth century Evans achieved international recognition as a fine art photographer, and his work has been firmly positioned in the canon of fine art photography since then. On the contrary, the RA/FSA file has assumed a complex position, stirring debates in the fields of history, sociology, documentary, and visual art. When evaluating the narrative of images produced by Evans as art, it is necessary to bear in mind the aforementioned facts and the context of the Depression era America in which he worked. Evans unquestionably viewed the RA/FSA position as a practical means to insure both his artistic and personal livelihood. Although Evans acknowledged that his work would be used for publicizing and legitimizing the Roosevelt administration, the period 1935-1938 may be conceptualized as a an expression of his subversive, artistic goals. He was given the status of senior photographer, accorded ample financial resources, given leniency from his superior, and produced images to satisfy his aesthetic vision. Assessment of the files produced by Evans reveal the work of a self-conscious and motivated artist who prioritized his own goals before he adhered to that of Stryker’s. Interestingly, Stryker was fully aware of Evans’ attitude towards his creative aesthetic and the RA/FSA:

“Evans was to disappear for months at a time, keep no clear records of where he had been or was going, and finally to reappear with a small number of the finest photographs ever taken. For two years Evans was allowed to set his own pace and the results certainly justified the patience. No one ever took better photographs than Walker Evans. On the other hand, Evans’ approach to photography made life difficult in a government bureaucracy.”14

Evans’ attitude reveals a definitive level of artistic independence, and the images he produced reveal a firm disinterest in the reportage and formalist representation styles evidenced in the works of other RA/FSA photographers. The most obvious element evidenced in the files which corroborates the art narrative in Evans’ work is the sense of distanced frontality, where objects, buildings, and persons are seen in direct and unflattering assuredness. Furthermore, the images are artistic rather than reforming, and communicate ideological observations on an array of conditions (industrial, rural, domestic, commercial, recreational). Jack F. Hurley has also presented arguments that support Evans’ work with the RA/FSA as art. Hurley notes that Evans consistently produced outstanding photographs which helped set the standard of excellence that affected anyone who joined the Historical Section, and this standard consisted of his work being “consistently of the very highest technical quality carrying an unmistakable message”.15 Evans’ headstrong practice of his aesthetic produced a number of files that strongly invoke the art narrative: the Erosion file, the Bethlehem-Pennsylvania file, and the Charleston-South Carolina file.

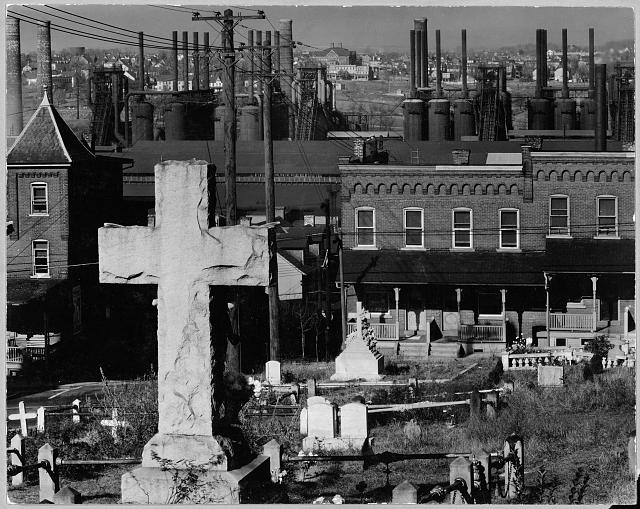

Although the art narrative in the RA/FSA file has been subject to controversial debate, the images produced by Evans indubitably substantiate the claim. A close examination of the Erosion file reveals Evans’ aesthetic and stance of artistic independence. The image Erosion Near Jackson, Mississippi (1936)16 is indicative of the greater file. The image is stark and frontal without an imposing style intruding between the image and the viewer. Stuart Kidd has remarked on Evans’ Erosion file stating that he “did not follow Stryker’s directives to photograph erosion, he produced formal studies of configurations of damaged land, notable for their shapes, line, and patterns”.17 The image Bethlehem Graveyard and Steelmill, Pennsylvania (1935) is exemplar of the file he created while on assignment in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The image is remarkable for its tonality, and in the context of the art narrative, its greater value lies in communicating Evans’ anonymity and refusal to endorse Stryker’s prescriptions.

In the Charleston-South Carolina file, Frame House, Charleston, South Carolina (1935) further supports Evans’ position as an artist and his images as art. The image, like other images contained in the Charleston-South Carolina file, transmits Evans’ anonymity; an emphasis on the formal study of architecture is prioritized above the documentation of social conditions concurrent to the times. The aforementioned photographs also embody Evans’ vision to explore the American vernacular in everyday culture.

Although Evans was criticized for the unorthodox approach he took with his RA/FSA assignments, his ability to produce remained unhindered. Evidence of Evans’ art narrative culminated in the form of solo show held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York: Walker Evans: American Photographs (1938). The exhibition was also presented in book format, featuring an influential essay by Lincoln Kirstein. The exhibition was presently independently of the RA/FSA though numerous images were extracted from the file. Stryker later commented that “certainly we had some artists working for us. Walker Evans thought of his work as art, and to prove it, had a one man show at the Museum of Modern Art.”18 The validity of the art narrative is authenticated by the fact that Evans was able to present a solo exhibition featuring images from the RA/FSA file.

Interior of a Coal Miner’s Home with Rocking Chair and Advertisements on Wall, West Virginia, 1935 (RA/FSA image featured in American Photographs Exhibition, 1938)

Images as Social Documentary

The RA/FSA file in its totality may be considered as one part of the greater discourse on documentary photography. Evans position within that discourse may be interpreted by the facts which have already been made evident: Evans, as artist, enabled an art narrative. However, this estimation of his character and the images he produced fails to account for the considerable social documentary narrative that was actualized in several files worthy of attention, namely the Hale County-Alabama and Arkansas files.

Evans’ preoccupation with the quotidian in vernacular American culture included the documentation of human responses to contemporary social conditions. At the forefront of 1930s documentary practice was the production of the documentary book. Evans social documentary narrative is illuminated by the file for the work Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. In 1936, Evans and Agee had originally traveled to Hale County, Alabama to produce an assignment commissioned by Fortune magazine about the lives of white sharecropping families. Stryker granted Evans a necessary leave of absence on the condition that the negatives would become part of the RA/FSA file. The qualitative value of the work was ideologically incompatible with Fortune’s editorial mandate, and it wasn’t until 1939 that the work was published by Houghton Mifflin. Evans’ Hale County-Alabama file became property of the RA/FSA, and thus entered the social documentary narrative. Evans, commenting on the images selected for Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, stated:

“some people think that all photography is inherently importunate, particularly that of people where they’re invaded by the camera. I get over that by feeling that it’s in the great tradition of documentary photography and that it isn’t really harmful.”19

The persuasive qualities of the images found Let Us Now Praise Famous Men stand in sharp contrast to the obvious art narrative illuminated in the Erosion, Bethlehem-Pennsylvania, and Charleston-South Carolina files. Evans’ social documentary narrative is punctuated by an involved and empathetic expression of the human condition, evidenced by his striking documentation of the lives of the Gudger, Woods, and Ricketts families. Evans’ images in combination with Agee’s text reveal a telling and unusual portrait of agricultural tenancy and New Deal policies in 1930s America. In the face of ubiquitous Depression era hardships, the work reconstructs the personal perspectives of three families in the lowest ebb of the economic ladder. The sharecroppers are unrelieved by New Deal policies ostensibly aimed to alleviate their distress, and the work is underscored by a sense of beauty in the face tragedy. The quality of beauty is a reoccurring theme in Agee’s text and Evans’ images.20

The qualities of persuasiveness and beauty make Let Us Now Praise Famous Men unique among other concurrently produced documentary books. Evans’ concentrated effort on portraiture in the presence of hardship supports the social documentary narrative. The portrait of Allie Mae Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama (1936) is exemplar of the greater Hale County-Alabama file. The portrait reveals Evans’ direct and frontal approach to social documentary and stands as iconic within the canon of 1930s documentary. It is pertinent to note that Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was in contemporaneous production with other documentary books, many of which were produced with the efforts of other RA/FSA photographers.21 William Stott, in his seminal work Documentary Expression and Thirties America, has regarded Let Us Now Praise Famous Men as the apogee of the documentary movement which transpired during the 1930s, stating that the text “culminated the documentary genre and breaks its mold.22 Evans’ empathy towards the human condition is also noticeably evident in the Arkansas file. Evans had been given explicit orders to document the Arkansas flood refugees, and a significant number of his images invoke the sense of a dual tragedy: flood victims who also bear the plight of the African-American experience. The image Negroes in the Lineup for Food at Mealtime in the Camp for Flood Refugees, Forrest City, Arkansas (1937) reveals Evans’ social and moral sensitivity to his subject in an artistically abstract manner. The flood refugees are photographed in profile from torso to just below the knees; their faces not visible. A chipped bowl and an aluminum plate dominate the image, detaching the individuals from the greater context but also emphasizing urgency and the human need for sustenance. Cara Finnegan has remarked on the comprehensive quality of Evans’ image, stating that:”depicting the universal need for sustenance embodied in the hands of black Americans offered the 1930s equivalent of the poorest of the poor. He does not show their faces, but their need is clear: their bowls are empty, they are hungry.”23

The images in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and the Arkansas file reveal an obvious social documentary narrative suggestive of the artist’s command in how he publicly exercised both his state of social consciousness and aesthetic.

Images as Propaganda

Although the images which support the art and social documentary narratives elucidate the elasticity of Evans’ practice, the dominant narrative espoused and disseminated by the RA/FSA was one of propaganda. The RA/FSA worked vigorously at producing materials that were didactic and illustrative of both Stryker’s vision and the Roosevelt administration’s efficacy. Reports, exhibitions, and countless publications such as Life, Look, and Survey Graphic featured images produced by the RA/FSA that were subject to government impulses and agenda. The intent of the RA/FSA’s dissemination strategy was purely propagandistic, and subtle advocation of specific responses customary. Although Evans refused to fulfil Stryker’s prescriptions, Evans’ association with the RA/FSA poses a valid reason to explore his practice within the propaganda narrative.

Images from the first major RA/FSA exhibition, held at the San Diego Exposition (1936), were expressed in the form of didactic rhetorical collages designed to substantiate both the RA/FSA’s and the New Deal’s cause. The presence of Evans’ work in this exhibition is a metaphor for the general involuntary posture he took towards the manipulation and dissemination of his work by the RA/FSA.It is perplexing to position Evans within the propaganda narrative given the evidence of the art and social documentary narratives and the fact that the RA/FSA file generally falls under the rubric of both social documentary and propaganda. Perhaps it is most applicable then to examine the images that Evans created directly for Congress and official reports in Washington. The files which reflect documentation of the RA/FSA’s subsistence homestead project efforts (Arthurdale Project file and Westmoreland Project file) and the Tennessee Flood file are relevant for consideration.

Under the New Deal, rural farm colonies and industrial settlements were envisioned as a middle class movement for selected applicants. The projects were ostensibly experimental and utopian, and soon proved to be costly failures in suburban planning. The one experiment which caught public attention was the Arthurdale Project, Reedsville, West Virginia. Financed by Lady Roosevelt and Louis Howe, by the late 1930s it proved to be an expensive failure.24 Given the time period in which Evans’ assignments were given (1935), the manner in which he chose to document both the Arthurdale and Westmoreland projects reveals his disengagement with Washington and the greater goals of the RA/FSA. The images Homes and Land Cultivation, Arthurdale Project, Reedsville, West Virginia (1935) and Westmoreland Project, Westmoreland Pennsylvania (1935) aptly illustrate Evans’ focus. Both images, also exemplar of the files, reveal a concentration on the artistic value of subject, where the mindful juxtaposition of architecture and landscape supersedes the social context.

The Tennessee Flood file is also noteworthy for examination as it marks Evans’ last complete narrative with the RA/FSA. In February of 1937, Evans’ had been sent to Tennessee to document government relief efforts following the Mississippi Flood . The images The Bessie Levee Augmented with Sand Bags during the 1937 Flood Near Tiptonville, Tennessee (1937) and Farmyard Covered with Flood Waters Near Ridgely, Tennessee (1937) reveal the work of a reflective, disinterested individual whose communing with natural disaster had provoked an opportunity for artistic exploration. Evans’ insistence to produce images incompatible with the RA/FSA’s propagandistic canon led to his dismissal. In March of 1937, when a reduction in budgetary expenditure arose, Evans was the first photographer discharged.25

Images in the Arthurdale Project, Westmoreland Project, and Tennessee Flood files reveal the intellect of an astute artist in command of his aesthetic who rejected the RA/FSA’s desired form of production. Bearing the three narratives outlined, it is opportune to note that Evans’ wrote a handwritten draft memorandum regarding his RA/FSA position in the spring of 1935, prior to his first assignment. The draft reads:

“Never under any circumstances asked to do anything more than these things. Mean never make photographic statements for the government or do photographic chores for gov or anyone in gov, no matter how powerful–this is pure record not propaganda. The value and, if you like, even the propaganda value for the government lies in the record itself which in the long run will prove an intelligent and farsighted thing to have done. NO POLITICS whatever.”26

As a primary source, the document synthesizes Evans’ awareness of the reality in which he was about to embark, and an awareness of the three narratives he would have to contend with. Evans’ disagreements with Stryker and the type of images he produced were political statements in their own right, and possibly an outward rejection of the Roosevelt administration in its entirety. It is plausible then to interpret Evans dismissal from the RA/FSA as a necessary termination of an artist in residence who was ideologically opposed to his employer. Evans’ propaganda narrative offers a fascinating discourse worthy of further discussion.

The ascension of a body of work to the status as national treasure does not deter the necessity for discourse. In the case of Evans’ contributions to the RA/FSA file, the complexity of the narratives continues to increasingly accumulate over time. Consideration of Evans’ art, social documentary, and propaganda narratives broadens our understanding of the RA/FSA file, and offers valuable insight into the artist’s personal world during a particular period in time. Consideration of Evans’ identity as an artist, the socio-economic conditions of the Depression era, and the political climate of the Roosevelt administration are essential to further comprehending the narratives.

Evans’ autonomy over his subject matter and aesthetic, his absolute rejection of Stryker’s prescriptions, and the breath of independence with which he continuously worked give both his character and images unique stature within the RA/FSA file. As a consequence, an unusual wealth of narratives are evident offering much to the development of discourse on the RA/FSA file and Evans. Images in the Erosion, Bethlehem-Pennsylvania, and Charleston-South Carolina files substantially reveal the artist’s narrative while the Hale County-Alabama and Arkansas files reveal the work of a skilled documentarian. His reluctance to produce accounts of government presence for the Arthurdale, Westmoreland, and Tennessee Flood files reveals his posture towards propagandistic production methods. All the while, Evans exerted his vision of a vernacular American culture within the framework of a bureaucratic agency. Working within a framework of contradictory impulses exacerbated by the conditions of the Depression, Evans balanced his artistic impulses and vision. Between 1935-1938, he produced some of the most important documents in American history and his extraordinary capabilities in the field of photography were revealed. The narratives presented here have been constructed not as arguments of persuasion but as tools for reading Evans’ work and the RA/FSA file.

Endnotes

[1] Given the inquiry in this essay is confined to the years 1935-1938, the nomenclature used to refer to the Resettlement Administration [RA] (1935-1937) and the Farm Security Administration [FSA] (1937-1942) will collectively be referred to as the RA/FSA.

[2] Allan Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation),” in Photography, Current Perspectives, ed. Jerome Liebling (Rochester, NY: Light Impression Corp., 1978), 236.

[3] Peter Turner, The History of Photography (London: Hamlyn, 1987), 103-104.

[4] Belinda Rathbone, Walker Evans: A Biography (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995), 27.

[5] J.A. Ward, American Silences: The Realism of James Agee, Walker Evans, and Edward Hopper (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1985), 145.

[6] Between 1933-1943, a cluster of New Deal arts initiatives, enabled by the Roosevelt Administration, financially supported thousands of creative individuals. Notable initiatives included: the Public Works of Art Project [PWAP], the Works Progress Administration [WPA]‘s Federal Art Project [FAP], the Historical Section of the RA-FSA-OWI, the Federal Writers Project [FWP], and the Federal Theatre Project [FTP]. John Raeborn writes that nearly 70 percent of New Deal agencies employed photographers within their programs and maintained pubic information offices to disseminate their pictures. None of the other agencies matched the visibility the RA-FSA-OWI received. The obvious reason for the RA-FSA-OWI’s visibility was that they employed talented photographers who made arresting pictures that media agencies might publish, whereas those who were employed by other agencies were mostly journeymen content with being employed. See John Raeborn, A Staggering Revolution, A Cultural History of Thirties Photography (Chicago: University of Illinois Press), 147.

[7] William S. Leuchtenburg argues that the inefficiency of the RA was the result of both the Roosevelt administration’s experimental planning strategy and the fact that the RA inherited the problems of its predecessor, the Federal Emergency Relief Effort [FERA]. The RA’s inefficiencies ranged from failure to adequately distribute available resources to barely processing a fraction of applicants. The focus of the RA had been to take land that had been exhausted by agricultural practices, lumbering, oil exploration, and drought, and to move 500,000 destitute persons situated within the dust bowl territory (the Southwestern United States). Only 4,441 families were resettled. As the ineffective nature of the RA was made public, Tugwell resigned from his post in 1936. In 1937, Congress passed the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenancy Act, and created the Farm Security Administration [FSA]. The RA transmuted into the FSA, and broader agency was accorded to program administrators. Under the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenancy Act, the FSA extended rehabilitation loans to farms, granted low-interest, long-term loans to enable selected tenants to buy family farms, aided migrants by establishing migratory labour camps, and amassed an incredible debt. According to Leuchtenburg, the FSA was the first agency to do anything substantial for the tenant farmer, sharecropper, and the migrant, however, he also points out that its main boast -the impressively high rate of repayment of its loans- suggested that the FSA did not dig very deeply into the problem of rural poverty. Furthermore, the FSA had no political constituency while its enemies, especially large farm corporations that wanted cheap labour and southern landlords who objected to FSA aid to tenants, had powerful representation in Congress. The FSA’s opponents kept its appropriations so low that it was never able to accomplish anything on a massive scale. See William Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and The New Deal, 1932-1940 (New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1963), 140-141.

[8]Stryker’s direction of the RA/FSA’s Historical Section was also influenced by his interest in the stabilization of a social welfare state and an awareness of the agency that photographic images carried. In 1925, Stryker had co-authored a text with Tugwell and Thomas Monroe entitled American Economic Life. His contribution was to find visual materials to illustrate the book, and in the course of doing so, he acquired knowledge of social documentary photography from Lewis Hine, who provided him with many of the book’s illustrations. See James Guimond, American Photography and the American Dream (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 110.

[9] An example of a portion of a select shooting scrip written by Stryker in 1936 reads as follows: From R.E. Stryker to All Photographers…Here again, a most interesting set of pictures could be taken, keeping in mind different income groups and different geographical areas…The group activities of various income levels, the organized and unorganized activities of the various income groups (Where can people meet? Both the well-to-do and poor). See Roy E. Stryker and Nancy Wood, In This Proud Land: American 1935-1943, As Seen in the FSA Photographs (Boston: New York Graphic Society Ltd., 1973), 187.

[10] RA/FSA file is held in the Library of Congress, and is referred to as the FSA/OWI Photograph Collection. It encompasses the approximately 77,000 images made by photographers working in Stryker’s Historical Section as it existed in a succession of government agencies: the Resettlement Administration (1935-1937), the Farm Security Administration (1937-1942), and the Office of War Information (1942-1944).

[11] Raeborn provides a critical evaluation of Stryker’s relationship with his photographers, and notes that both Evans and Dorothea Lange repelled Stryker’s hostility towards their artistic independency. Raeborn, A Staggering Revolution, 157.

[12] Years later, Evans described his tenure with the RA/FSA as a “great opportunity to go around freely at the expense of the federal government… and photograph what I saw in this country…I was exploiting the United States government, rather than having them exploit me…If I was asked to do some bureaucratic stupid thing, I just wouldn’t do it…I just photographed like mad whatever I wanted to. I paid no attention to Washington bureaucracy.” See Walker Evans, “Walker Evans, Visiting Artist: A Transcript of His Discussion with Students at the University of Michigan,” in Photography: Essays and Images, ed. Beaumont Newhall (New York: MoMA, 1980), 315, 317.

[13] Trachtenburg, a scholar in American Studies and prominent specialist on American photography, has published extensively on Evans. His writings have contributed remarkably in the process of promoting Evans as an artist. See Alan Trachtenburg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Matthew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989), 289.

[14] Roy Stryker, interview by Richard Doud, Montrose, CO, January 23, 1965. Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art.

[15] Jack F. Hurley, Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1976), 48.

[16] All images referred to in this essay are referenced from the Library of Congress, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives, www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsa/.

[17] Stuart Kidd, Farm Security Administration, Photography, The Rural South, and the Dynamics of Image Making 1935-1943 (Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellon Press, 2004), 68.

[18] Stu Cohen, The Likes of Us: America in the Eyes of the Farm Security Administration (Boston: David R. Godine Publisher, 2009), XX.

[19] William Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 283.

[20] James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1939), 202-203.

[21] Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1939) by Agee and Evans evolved from an assignment commissioned by Fortune magazine in 1936. Upon completion, the work’s content was deemed visually and ideologically incompatible with Fortune’s, and was subsequently published by the Houghton Mifflin Company in 1939. Contemporaneously produced photo books worthy of note are: You Have Seen Their Faces (1936) by Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White, Land of the Free (1938) by Archibald Macleish with Lange, Evans, Arthur Rothstein, and Shahn, An American Exodus (1939) by Paul S. Taylor and Lange, and 12 Million Black Voices (1941) by Richard Wright and Edwin Rosskam.

[22] Stott, Documentary Expression and Thirties America, 266.

[23] Cara Finnigan, Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photographs (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2003), 154-155.

[24] Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 136-137.

[25] Although Evans’ contract officially ended in September of 1937, he continued to work as an independent photographer with the RA/FSA until the summer of 1938. His final assignment was the New York, New York file. The Historical Section of the RA/FSA (which later became the Office of War Information [OWI] 1942-1944) continued to use Evans’ work in multifarious efforts directed at substantiating both New Deal policies and the United States war effort.

[26] Jerry L. Thompson and John T. Hill, eds., Walker Evans at Work (New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1971), 238.

Bibliography

Agee, James and Walker Evans. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1939.

Badger, Anthony J. The New Deal: The Depression Years, 1933-1940. New York: The Noonday Press, 1989.

Bezner, Lili Corbus. Photography and Politics in America From the New Deal into the Cold War. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1999.

Cohen, Stu. The Likes of Us: America in the Eyes of the Farm Security Administration. Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher, 2009.

Curtis, James. Mind’s Eye, Mind’s Truth: FSA Photography Reconsidered. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989.

Dixon, Penelope. Photographers of the Farm Security Administration: An Annotated Bibliography. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1983.

Evans, Walker. Walker Evans: American Photographs. New York: Doubleday, 1938.

Evans, Walker. “Walker Evans, Visiting Artist: A Transcript of His Discussion with Students at the University of Michigan.” In Photography: Essays and Images, edited by Beaumont Newhall, 311-320. New York: MoMA,, 1980.

Finnegan, Cara. Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photographs. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2003.

Fleischhauer, Carl and Beverly W. Brannan, eds. Documenting America, 1935-1943. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Guimond, James. American Photography and the American Dream. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Hurley, F. Jack. Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties: Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972.

Kidd, Stuart. Farm Security Administration Photography, The Rural South, and the Dynamics of Image-Making, 1935-1943. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellon Press, 2004.

Kirstein, Lincoln, “Photographs of America: Walker Evans.” In Walker Evans: American Photographs by Walker Evans, 187-195. New York: Doubleday, 1938.

Leuchtenburg, William E. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1932-1940. New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1963.

Library of Congress. Farm Security Administration/ Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives. www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsa.

Maddox, Jerald C., ed. Walker Evans: Photographs for the Farm Security Administration, 1935-1938. New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1973.

Raeburn, John. A Staggering Revolution, A Cultural History of Thirties Photography. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Rathbone, Belinda. Walker Evans: A Biography. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995.

Sekula, Allan. “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation).” In Photography, Current Perspectives, edited by Jerome Liebling, 231-255. Rochester, NY: Light Impression Corp., 1978.

Stott, W. Documentary Expression in Thirties America. New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 1973.

Stryker, Roy. Interview by Richard Doud. Montrose, CO: January 23, 1965. Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art.

Stryker, Roy E. and Nancy Wood. In This Proud Land; America, 1935-1943, As Seen in the FSA Photographs. Boston: New York Graphic Society Ltd., 1973.

Thompson, Jerry L. and John T. Hill, eds. Walker Evans at Work. New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1982.

Trachtenberg, Alan. Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Matthew Brady to Walker Evans. New York: Hill and Wang, 1989.

Turner, Peter. The History of Photography. London: Hamlyn, 1987.

Ward, J. A. The Realism of James Agee, Walker Evans, and Edward Hopper. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1985.